The patients that arrived

for treatment in mid-June at hospitals in Manzanillo had all gone to

the same birthday party held at a house in the hilly countryside on the

perimeter of the eastern Cuban city.

The sick had eaten shrimp

at the party and doctors thought that meal might be the cause for the

patients' heavy vomiting and diarrhea.

Then more people began walking into hospitals with similar symptoms.

But they had not attended the party.

Casos de cólera en Cuba

Casos de cólera en Cuba

"They started coming in a

few at a time," said Julio Cesar Fonseca Rivero, the director of the

Celia Sanchez Manduley Hospital, the largest in the region. "The first

day five came, and then eight. That's not normal, that five people would

come with the same symptoms. The most critical days were when there

were 30 to 32 patients who arrived in a single day."

A sudden spike in cases

of diarrhea is not unusual for Manzanillo's hospitals that treat the

surrounding rural communities. There residents often live without indoor

plumbing and in the summer months endure the scorching heat and heavy

rains.

This summer had already been particularly hot with heavy rains that caused outhouses to flood into several drinking wells.

Still, doctors suspected they were dealing with something they hadn't seen before.

"We became alarmed with

the number of cases arriving. We usually see one or two cases of

diarrhea each day," said Dr. Oyantis Matos Zamora, who oversees a clinic

on the edge of the city that attends to rural residents.

The symptoms some

patients exhibited -- the rapid onset of watery diarrhea and dehydration

— had also not been seen in generations.

"The way that the

outbreak developed and the appearance of other similar cases in the

region, we realized this was a problem of a different magnitude," said

Dr. Manuel Santin Peña, Cuba's national director of epidemiology.

The "problem" was cholera.

Cuba's last cholera

outbreak occurred over a century ago. Although eradicated in many

countries, the disease, according to the World Health Organization,

still infects between 3 million and 5 million people each year, killing

between 100,000 and 120,000.

In Manzanillo the outbreak has taken on a name of its own. There it's simply referred to by residents as "el evento."

So far "el evento" has

taken three lives and infected at least 110 people, said Santin. He said

doctors were waiting on test results for tens of other possible cases

but said so far fewer than 30% percent of suspected cases had been shown

to be cholera.

He denied reports that

the Cuban government has underreported the death toll or that the

outbreak is spreading to other provinces.

He said a handful of

suspected cases had been identified elsewhere in the country. But he

said those cases had come from the same region where the original

outbreak took place and are believed to have been infected there.

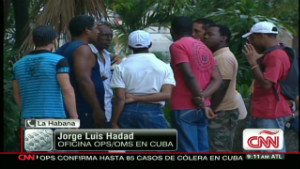

"We can categorically

say that there is no other outbreak in any other province," Santin told

CNN, outside the entrance to the Celia Sanchez Manduley Hospital, where

three more people had arrived suffering from severe diarrhea.

Cuban health officials

allowed a CNN crew to be the first media to film in the hospital and

speak with doctors there about the ongoing effort to control the cholera

outbreak.

To combat the outbreak,

the local government has closed 12 contaminated wells around Manzanillo,

Santin said. Clean water is being trucked in for residents until a

different source of water can be found.

At the entrances to

hospitals and government buildings in the city stand buckets for people

to wash their hands and soles of their shoes with chlorine bleach.

No comments:

Post a Comment